A One-Stop Shop for Infectious Disease Research

The latest COVID variant. A new strain of bird flu that has the potential to spread to humans. A bacterial infection that’s resistant to antibiotics. Each news cycle seems to bring with it new or renewed concerns for infectious disease researchers who are on the front lines battling threats to public health.

Essential to tamping down these threats is the development of vaccines, therapeutics, and medical diagnostics—and a team at the University of Virginia’s Biocomplexity Institute has been hard at work on a resource that provides the data, workspaces, and analysis tools to make fighting these battles a bit easier.

The Bacterial and Viral Bioinformatics Resource Center (BV-BRC), a beta website that launched in February, “is one-stop shopping for your bacterial or viral genomic research,” said Ron Kenyon, a senior scientist in the Network Systems Science and Advanced Computing division of UVA’s Biocomplexity Institute.

Essentially, the free resource is “helping advance medical treatment and the understanding of infectious diseases, the development of drugs and vaccines,” Kenyon said. “This site alone is not doing all that, but it’s a toolbox to help people who are on the front lines.”

The BV-BRC combines the data, computational tools, and technologies from three legacy centers used by the scientific community: PATRIC, which supplies bacterial data, and IRD and ViPR, which supply viral data. In 2019, the National Institutes of Health contracted with the University of Chicago to consolidate the three centers—housed on two servers—into one. UVA is one of the subcontractors and collaborators along with the Fellowship for Interpretation of Genomes and the J. Craig Venter Institute.

This new resource gives users access to comprehensive datasets—including more than 550,000 bacterial and 6.7 million viral genomes that are annotated and include hundreds of metadata fields—as well as tools to help analyze data and make predictions using artificial intelligence. While most of its users are infectious disease researchers, the site is also geared toward pharma companies, clinical researchers, epidemiologists, and those in academia.

Its tools are already changing the face of research. Take, for example, its ability to use machine-learning methods to predict antimicrobial resistance (AMR)—when an organism changes its genetic structure over time, making it immune to existing antibiotics. The BV-BRC can take a bacterial genome sequence and predict whether—like certain strains of staph and strep infections —how the isolate will respond to certain antibiotics. The predictions are based on countless bacteria that have been sequenced and determined to be susceptible or resistant to different antibiotics.

“When we get a new bacterial sequence in, just based on its genetic sequence, we can predict if it will be susceptible or resistant to any of those antibiotics,” Kenyon said. “If some new bacterial strain comes along and we don’t know what it is or if it’s different, we run it through this process and can say, ‘Oh, this strain looks like it’s going to be resistant, we better keep an eye on it, see if it’s spreading.’”

Another way the site is helping to tackle today’s public health concerns is by offering tools to break down the new coronavirus variants that continue to pop up two years into the pandemic. When the genome of the SARS-CoV-2 virus mutates, creating a new strain, researchers need to determine whether it might be more infectious or faster-spreading than the others. To do that, they can look at the DNA sequence and do comparisons using the BV-BRC’s tools.

Using the SNP analysis tool, researchers can line up the newly discovered sequence against the earliest Wuhan-1 sequence and those of the variants we’ve seen so far, like Omicron and Delta. Then they can compare them to see whether there are differences that might be concerning.

“What they are particularly worried about is the spike protein,” said Rebecca Wattam, a research associate professor in the Network Systems Science and Advanced Computing division at UVA’s Biocomplexity Institute who has been leading the BV-BRC outreach effort. “If a new variant of SARS has a change in the confirmation, the way that its spike protein looks, that would sail right past the immunity we have [from] the vaccine—that’s what they’re nervous about, that’s what they’re all looking for.”

‘A Boutique Resource’

This new BV-BRC isn’t just a combination of the three legacy sites, which will go offline in the fall after testing on the beta site is complete: It is faster, has much more data, and includes new and expanded tools for both bacterial and viral researchers.

“With the new unified site, there are functionalities and features and data that are not in the legacy sites by virtue of the fact we’re joining them together,” said Kenyon, whose primary role is in project management and software engineering.

One new shared tool that benefits the viral community is the comprehensive genome analysis. PATRIC had this tool for bacterial analysis, and when the sites merged, a similar tool was built for SARS-CoV-2. There’s also a new SARS-CoV-2 variant tracker on the website dedicated to the new mutations and their relative preponderance and timing.

The primary source of the BV-BRC’s baseline data is NCBI GenBank, the nation’s repository for DNA sequences. The BV-BRC takes that data, does additional analysis, and processes it in ways that make it comparable for its users.

“What we [are] is like a boutique resource,” Kenyon said. The BV-BRC “is geared very much toward the research groups they’re supporting, using terminology and workflow patterns that would be typical for a bacterial or viral researcher.”

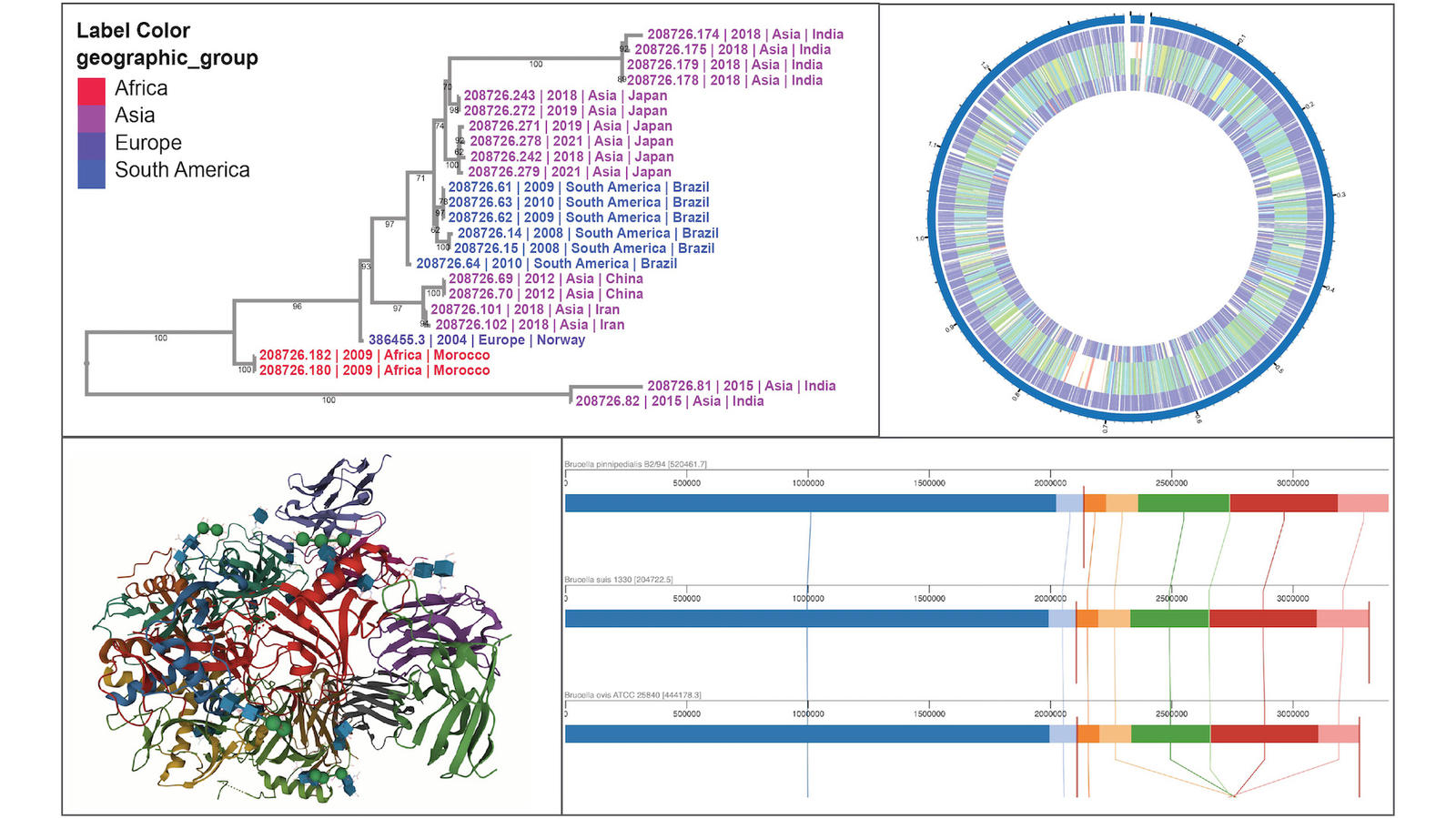

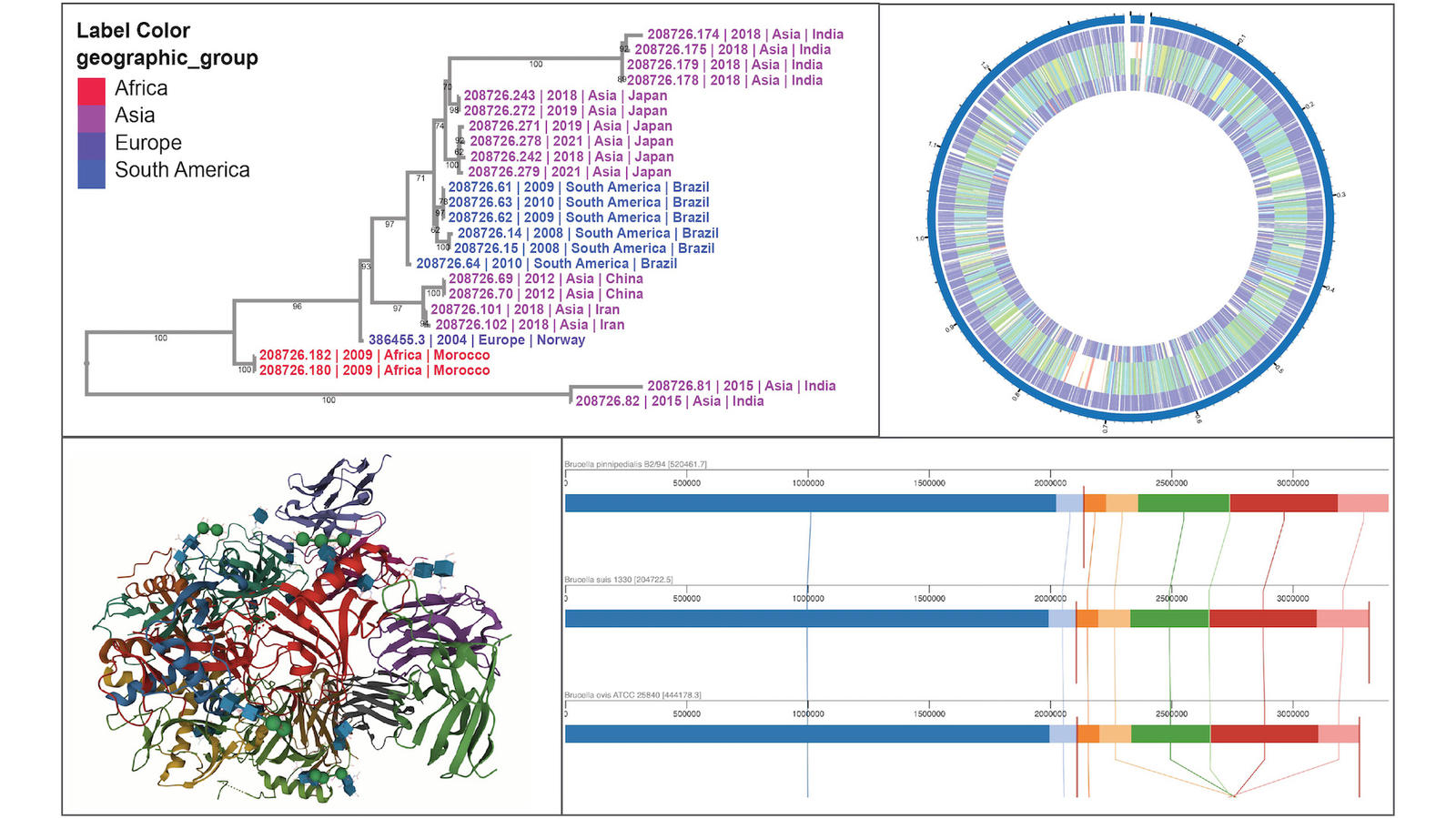

There are more than 30 interactive data analysis and visualization tools, including genome assembly, genome annotation, and phylogenetic tree analysis. There are several comparative genomic tools like sequence alignment and several new tools including a 3D protein structure viewer that offers a three-dimensional rendering of a protein that you can rotate and color-code.

Not only is the BV-BRC free, but researchers are also given free storage for their data and private workspaces where they can do their comparative analyses. They can share their results with others, generate reports and figures for publications, and ask questions through the site’s help desk.

Spreading the Word

Kenyon, Wattam, and their team at the Biocomplexity Institute have been working on the project for more than 15 years, helping develop and maintain the database (at the time, the PATRIC site, and now, the BV-BRC), building new analytic tools, and training users.

A significant part of the UVA team’s work has been reaching out to the scientific community and training researchers on what these sites can offer them. Up until a few months ago, they were training users on the legacy sites, but now they are helping existing users migrate over to the BV-BRC site as well as recruiting new users.

“We’re helping them understand how to use it—with all this data and the mixture of bacterial and viral data and we have 30 or more analysis tools, some of which are quite complex—to understand how those things work and how you can use them and how you can use them in your research,” Kenyon said. “People don’t want to use the site just to use the site; they have a research question in mind. How do I use this tool, this website, to answer my real question? So it’s helping people transform their research questions into analysis and then helping them interpret what the resource or the website is telling them.”

PATRIC, IRD, and ViPR are used extensively by the research community with about 32,000 registered users combined—those who have created free accounts and logged in. Last year, users ran roughly 30,000 analysis jobs a month using the research pipelines provided by these systems. While there are only a few thousand currently using the new BV-BRC site, the outreach effort is ramping up with announcements on the existing sites, notifications sent to users, social media posts, and quick-start videos on how to search and filter data and submit and review the results of analysis jobs.

Wattam teaches an online training course for the website and holds workshops and webinars. During those sessions, she has seen how researchers tend to pull down different pipelines to run their data and then struggle to interpret the results. Many are amazed when she shows them how, with the BV-BRC, they can do their analysis in one place—for free.

With the BV-BRC, there is no need to spend weeks or months manually analyzing data.

“When we did the first genome annotation, before we had pipelines, we were able to annotate a genome and it took six months—and that was with a team of people working on it,” Wattam said. Now—with the BV-BRC—“you can do it in minutes.”